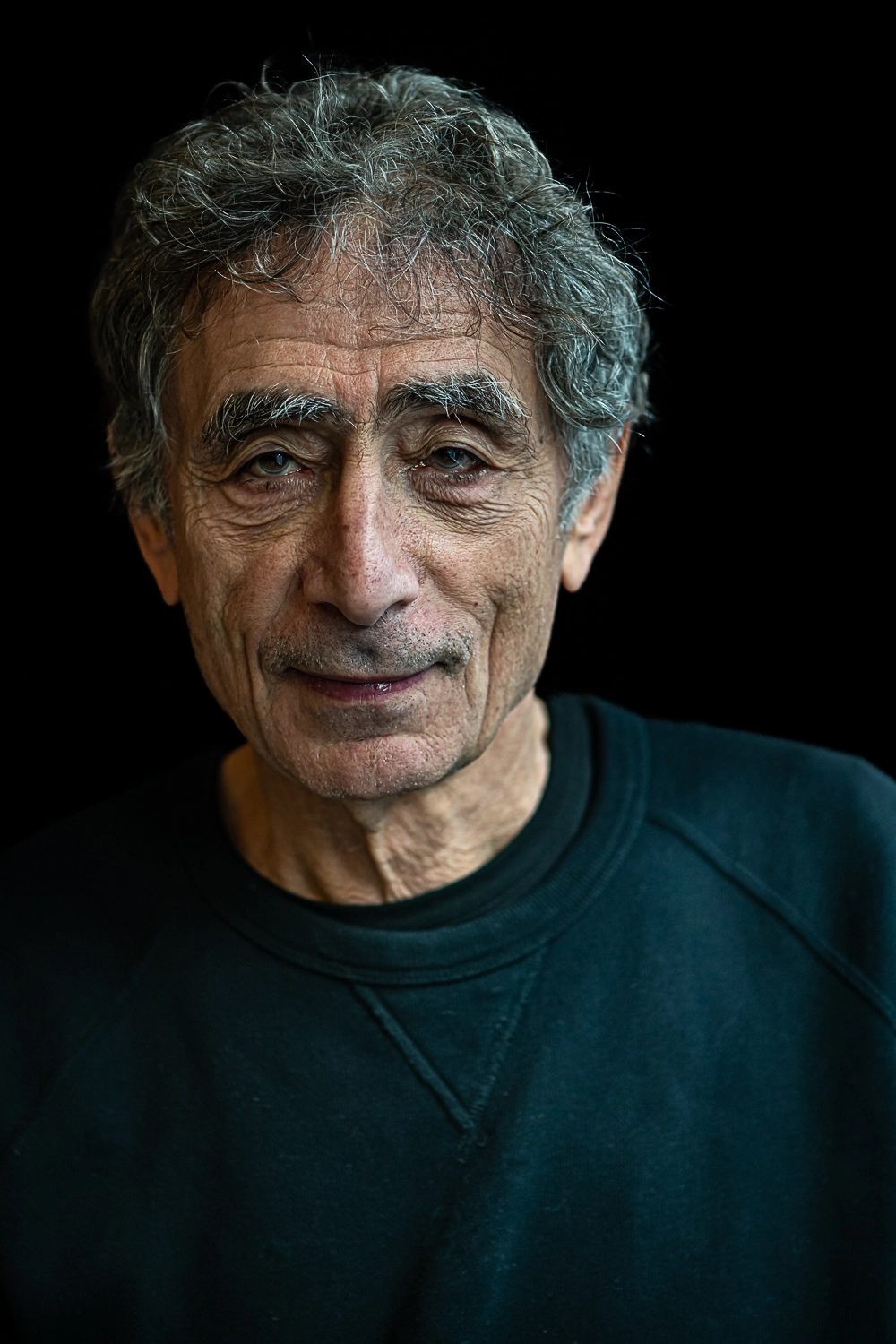

Gabor Maté is a retired physician who, after 20 years of family practice and palliative care experience, worked for over a decade in Vancouver’s Downtown East Side with patients challenged by drug addiction and mental illness. The bestselling author of four books published in thirty languages, including the award-winning In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction, Gabor is an internationally renowned speaker highly sought after for his expertise on addiction, trauma, childhood development, and the relationship of stress and illness. For his groundbreaking medical work and writing he has been awarded the Order of Canada, his country’s highest civilian distinction, and the Civic Merit Award from his hometown, Vancouver. His fifth book, The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness and Healing in a Toxic Culture will be released on September 13, 2022.

422: The Myth of Normal Parenting

Gabor Maté, MD

Dr. Gabor Maté talks to us about how to reconnect with your feelings, trust your instincts, and help kids express emotions in healthy ways.

The Myth of Normal Parenting - Gabor Maté, MD [422]

Read the Transcript 🡮

*This is an auto-generated transcript*

[00:00:00] Gabor Maté, MD: What I'm saying is that very often the things we take for granted in our society may be the norm in the sense that it's the behavior or the values that prevail, but they're neither healthy or natural.

[00:00:19] Hunter: You're listening to the Mindful Parenting Podcast, episode number 422. Today, we're talking about the myth of normal parenting with Dr. Gabor Mate. Welcome to the Mindful Parenting

Podcast. Here, it's about becoming a less irritable, more joyful parent. At Mindful Parenting, we know that you cannot give what you do not have, and when you get calm and peace within, then you can give it to your children. I'm your host, Hunter Clark Fields. I help smart, thoughtful parents stay calm so they can have strong, connected relationships with their children.

I've been practicing mindfulness for over 25 years. I'm the creator of the Mindful Parenting course. And I'm the author of the best selling book, Raising Good Humans, a mindful guide to breaking the cycle of reactive parenting and raising kind, confident kids, and now raising good humans every day, 50 simple ways to press pause, stay present, and connect with your kids.

Welcome back to the Mindful Mama podcast. I'm so glad you're here. Make sure, of course, you are subscribed so you don't miss any of these awesome episodes that drop every Tuesday. And of course, it would be amazing if you get some value from this podcast, if you could just take a few seconds and go to Apple Podcasts, right, where you're listening to this on the app, and leave a quick review.

It makes such a big difference. And today is super exciting in just a minute. You're gonna hear me sit down with Dr. Gabor Mate, a retired physician who, after 20 years of family practice and palliative care experience, worked for over a decade in Vancouver's downtown Eastside with patients challenged by drug addiction and mental illness.

He's a best selling author of four books, published in 30 languages, internationally renowned speaker, and highly sought after for his expertise on addiction, trauma, and childhood development and the relationship of stress and illness. His books include In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, When the Body Says No, The Cost of Hidden Stress, The Origins and Healing of Attention Deficit Disorder, Gordon Neufeld's Hold On to Your Kids, Why Parents Need to Matter More than Peers, and his book out now is called The Myth of Normal Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture, and this is what We talk about this conversation was originally aired in the Raising Good Humans Every Day Summit, the Raising Good Humans Summit.

And you're going to hear us talk about my childhood. He talks to me about what it was like for me to be spanked as a child and how it affected me and childhood development in general. So we're going to talk about what is this idea of normal parenting. It isn't normal necessarily good. We're going to talk about how to reconnect with your feelings, how to trust your instincts, and help your kids express emotions in healthy ways.

This is a really, really powerful episode. I hope you enjoy it. Before we dive in, I want to mention that you can, of course, listen to this episode ad free by becoming a subscriber of Mindful Parenting Podcast Plus. You would get the same episode in your feed just without ads. And you can do that, become a supporter of this podcast by going to MindfulMamaMentor.

com and on the podcast link. All right, let's dive in. Join me at the tables I talk to, Dr. Gabor Mate.

Gilbert Montay, thank you so much for coming on the Raising Good Humans Summit. It's really an honor for me to talk to you. I'm so enjoying the myth of normal. Thank you so much for coming on.

[00:04:10] Gabor Maté, MD: Pleasure. Thank you for having me.

[00:04:12] Hunter: Well, I'd love to just kind of start out with the book, the title, the myth of normal.

What do you mean by the myth of normal?

[00:04:19] Gabor Maté, MD: Well, um, usually when we employ the word normal, we mean something that's natural, to be expected, healthy, and as a physician, I'm trained in, um, understanding the normal parameters of livable existence, so that within a normal range of temperature, human life is possible.

Outside of it, it's threatened. Normal range of blood pressure. So what is normal is identical with healthy and natural in the physiological sense. But of course, normal, uh, in our society is also used to refer to something that we're used to, so accustomed to, that we just think that's the way things have to be.

So, for example, um, when we say, uh, somebody's being selfish, we say, well, that's just normal, you know, or, or, um, the fact that people, uh, women, for example, take on more emotional work than men do, we say, well, that's normal because we're used to it. But what I'm saying is that very often the things we take for granted in our society may be the norm in the sense that it's the behavior or the values that prevail, but they're neither healthy or natural.

So much of what we consider to be normal, like, for example, in our society, you're interested in raising good humans. It's very normal in this society not to pick up kids when they're crying. Parents will ignore it, sleep training, don't pick up the baby. Or, it may be normal to give a kid a time out, whereas if you're going to be upset, you're going to have to be on your own.

It's normal. We're all used to it. Experts advocate for it. It's completely unhealthy and unnatural. It undermines our capacity to raise good humans. It's what babies really need and young children really need. It's connection and contact and physical proximity and emotional acceptance. So a lot of the parenting behaviors, I'm just giving you one small example of how we use normal.

They're normal in the sense that they're the norm, but they're unhealthy and unnatural and have very negative consequences on human development. And

[00:06:36] Hunter: these would be like the, the negative consequences you're talking about. These would be kind of like the small T traumas. And you talk in, in the myth of normal, you talk a lot about how we grow up and the things that we think are normal that are actually.

Not very supportive of mental health and emotional health and well being that are considered normal, and you mentioned a couple of them, but like, you know, timeouts are incredibly normal, right? You know, even if we're, even if we're now, like, maybe a little bit more like picking up the babies, but now, you know, with the toddlers, I see it all the time that, oh, he needs, he just needs to calm, he just needs to have some time by himself to calm down.

But. You point to the research and the The, the learnings that this is actually, these are, these contribute to these kind of what you call kind of like these small T traumas for kids and have repercussions as we grow up or as kids grow up.

[00:07:33] Gabor Maté, MD: Yes. So trauma, he probably understood, is not a terrible event.

That's not what the word trauma means. Trauma literally comes from a weak word for one day. So trauma is a kind of wound that hasn't healed yet. Now you can wound people by imposing on them terrible circumstances, such as sexual abuse or severe beatings, the loss of a parent through a divorce, or mental illness, or eviction, or violence in the family, or even a rancorous divorce.

These are big, deep traumatic events. But you don't need these big events, like a tsunami or a war, um, or severe abuse and neglect. To warn kids, you can warn children just by not meeting their needs. But being physically picked up is a need of the small child for the healthy development of their brains and their senses.

So, in the mammalian world, you never see a mother cat or a mother bear or a mother orangutan ignore the distress of a child. But human mothers and fathers are told, ignore it, let them get over it on their own. It goes contrary to human needs. to human nature, because as a mother or a father, your heart is crying out to pick up the child, but you've been told by all these experts not to.

So it's norm not to, but it's completely unethical and unnatural. And so that what has become normal in our society is for parents actually to become disconnected from their parenting instincts. And, and, and now we're parenting not from our gut feelings and our heart, but we're parenting from A perceived need to impose certain behaviors on a child, which undermines the child's healthy sense of self, sense of trust in the world, um, interferes with their brain development, and wounds them psychologically.

This is what I call the small T traumas. Those, those small T. Events that we take for granted, but they're wounding to the child. And I've talked to so many people. I mean, they, you know, they had addictions or mental health conditions or physical health issues, I think it's all related, but I had a totally happy childhood, you know, and then I speak to them for three minutes and the wounding becomes very apparent, but since they think it's normal.

They don't think of it as one thing.

[00:09:59] Hunter: Yeah. And it's interesting because I, it's like I can mention, it's very frustrating for parents because some of the things that we think of as like, as our instincts and are actually may be our instincts, right? To pick up our child and things like that. But then some of the things are habit energies or just traditions and things that are unhealthy that are passed down to us that feel like our instincts, right?

That, and it's hard for parents to discern what is healthy and what is not because we have You know.

[00:10:30] Gabor Maté, MD: I understand what you mean. I don't think it's as hard as you might imagine because ask any mother or father when they're not picking up their child and they may think it's the right thing to do. What are they experiencing in their bodies?

Is there peace? Incredible

[00:10:48] Hunter: distress. Yeah.

[00:10:49] Gabor Maté, MD: That's the, that's the nature of telling them that it's not, you're a natural. We've been taught to ignore ourselves. One of the impacts of trauma is to get disconnected from ourselves. It's true. When parents get disconnected from their own feelings, it makes you write to them to do a certain thing.

Ask them what's going on in their bodies. There's usually tension there.

[00:11:13] Hunter: Yeah, I think, I think you're right. Like, these emotions and tensions, these are messengers that are telling us something incredibly important. You know, with the idea of trauma, many of us experience all kinds of traumas in our childhood, and I know From your story, you know, you experienced like real, some of those real big T traumas and thinking about other people in their story, you know, I'm one of those people who said, oh, you know, my, my father spanked me and I, I remember that and that's like, but I'm, I had a pretty happy childhood and normal and things like that and that was normal at the time and by that, I've talked to him about that and he's talked about the abuse that he suffered from his father, right?

And how these things kind of get passed down. Yeah.

[00:11:57] Gabor Maté, MD: How old were

[00:11:57] Hunter: you when you were spanked? Oh, like five years old. You know, whatever age. Yeah.

[00:12:04] Gabor Maté, MD: What did that what you call spanking look like? If I was watching it, what would I be seeing?

[00:12:10] Hunter: I would be cowering behind the door of my bedroom, totally scared as he raged down the hall to come get me.

[00:12:18] Gabor Maté, MD: And when he spanked you, what would I be seeing, if you're willing to share?

[00:12:23] Hunter: Probably me crying and screaming

[00:12:26] Gabor Maté, MD: and... What would he be doing? He

[00:12:30] Hunter: would be angry, be hitting me on my bottom.

[00:12:34] Gabor Maté, MD: Why do we call it a speck? It's hitting. I know. Okay, number one. Number two. You got kids? Yeah. Two girls. How old are they now?

Thirteen, sixteen. Can you imagine either one of them at age five? Yes. Now, try and put them into the scenario that you're in. Their father is raging and hitting them. What are they experiencing? Well,

[00:12:57] Hunter: I could see that when I, cause that temper came out in me, not in hitting, but in yelling. And I could see the fear in my oldest daughter's face when she was two and just see how terrible it was.

I mean, that was what drove me to write the books.

[00:13:12] Gabor Maté, MD: And, and just as I've learned from my own parenting, full pause, you know, I mean, literally I've made every mistake in the book, including in my own books, you know, so we're not judging anybody here. We're just trying to look at the experience of the child.

[00:13:30] Hunter: Stay tuned for more Mindful Mama podcasts right after this break.

[00:13:38] Gabor Maté, MD: When you were five years old and terrorized, cowering in fear, who would you speak to about it? No one. If you're five years old, that's fear. What would you want her to speak about it? I want her to

[00:13:50] Hunter: talk to me about it. Her dad.

[00:13:52] Gabor Maté, MD: Okay, if your five year old had fear and terror and didn't talk to you about it, how would you explain that?

[00:13:59] Hunter: Mmm, I mean, yeah, that's an intense disconnection, I think. I guess that's how I would look at it. And

[00:14:08] Gabor Maté, MD: how would that leave the child feeling to be in a sense disconnected from, you know, I'm, I'm, I'm not questioning whether or not your parents loved you. I'm talking about the wounding that happens even in loving homes.

By age five, the day you were born, if you were upset or unhappy, did you communicate it, do you think? If you had fear or... The stress that you communicated? Yes, definitely. What happened between Angel day one and, and year five is you learned that you're completely all alone without help.

[00:14:39] Hunter: I think I communicated, I think I was pretty, like I, I expressed some intense hatred at that moment in a lot of moments that, around moments like

[00:14:49] Gabor Maté, MD: that.

Well, that's good, but I just asked you, who did you communicate to fear to? Yeah. Nobody. Mm-hmm. . What is it like for a child to be that alone, that they can't communicate their deepest fears? What does it feel like for a child?

[00:15:03] Hunter: Oh man, I want to just rock. Poor little, little hunter for that. I mean, that's

[00:15:09] Gabor Maté, MD: horrifying.

Horrifying is the word you used. I didn't, it was your word. There's your happy childhood. And there's the happy childhood of a lot of people. So you ask them, what's it like to have a normal childhood? Yeah, that's the whole problem.

[00:15:23] Hunter: Oh, wow. So, yeah, I mean, I think about that too, like, these traumas and these, the suffering, right, that has been passed on to so many people and, you know, much, you know, bigger, more intense traumas as well as these every, what we'd call my experience and everyday kind of trauma.

And then now we're in a place where we as a generation, I think, of parents are really trying to sort of turn things around. So maybe we could talk about what are some of the things that children do need for that sense of security, that sense of well being and emotional healthiness and groundedness.

[00:16:02] Gabor Maté, MD: Well, you were kind enough to mention my book, The Myth of Normal. There's a chapter called, A Sturdy or Fragile Foundation, Children's Irreducible Needs. By an irreducible need, I mean a need that if met, it leads to health and, and, and optimal development. If not met, it leads to wounding and dysfunction.

You have an irreducible need. You have an irreducible need for oxygen. If all of a sudden, someone deprived the space that you're in from oxygen, you'd be in deep trouble. Our need for oxygen isn't some kind of an arbitrary quality, it's a nature given need. Nature has created us in response to oxygen. If it wasn't for oxygen, it wouldn't exist.

So that it's an irreducible need. As we evolve as human beings, we've also evolved certain irreducible emotional needs, without which, unlike without oxygen, we can actually survive, but we will not be optimal, we will not be healthy. Human beings can adapt, but adapting doesn't mean functioning optimally or in a healthy way.

So what are the irreducible needs of children? Number one, unconditional loving acceptance and relationship in which to feel completely secure and welcome for being who they are. That's the first needs of the child. Second, the irreducible need of the child is the, or my brilliant friend, the psychologist Gord Neufeld called rest.

And rest means that the child shouldn't have to work to make their relationship work. To give a very common, but perhaps extreme example, in a home where a parent is an alcoholic, often a child takes on the role of caregiving to the mother or to the father or both. Now that means that the roles are reversed and the child is happy to work to preserve that atmosphere in a home.

Or, if the parents listen to the advice of any number of completely misinformed parenting experts, that anger in a child should be punished, that temper tantrum should be punished, then the child learns, in order to be acceptable to the parent, I have to suppress myself. And it takes a lot of work to suppress your anger, a lot of work, so the child is working not to be themselves, for the sake of being acceptable to the parents.

The child needs to have rest, not to have to work. That's the second need. The third need is we are endowed by nature with a certain set of emotions. From rage, to um, to from anger, to joy, to playfulness, to curiosity, to grief, to fear. We have to be able to experience all those emotions in order to grow up properly.

Not that parents have to impose on them on the child, the child will experience them. A dog, a pet will get lost, will die, a grandparent might die. A neighbor or child may not want to play with you. You're going to have grief. You have to be able to experience that grief. You have to be able to experience the anger when you're frustrated.

Um, we share these circuits with other animals. And for healthy development, we have to be able to experience them, and parents have to hold us in a way that we can regulate those emotions. Not to suppress them, not to have them, but to be able to be with them. And that's the third irreducible need. The fourth one has to do with play.

Spontaneous, free play, art in nature, with multiple age playmates. Which is insanely how we evolved as a species for millions of years. It's how cats evolve, dogs evolve. Play is usually important. One year olds with this, they're not playing. This is not a spontaneous free play with other kids. And so those are the irreducible needs.

When we're interfering with them, it's very normal in our society, but it undermines healthy development.

[00:20:09] Hunter: We want that loving acceptance, acceptance of who they are, that, the, the, the ability to express all the different emotions, and, and those, and then. Face, rest, rest to be who they are and not have to do the work in the relationship.

And then this incredible, valuable, free play. Yeah. I mean, to me, that sounds amazing and it sounds so you're right. Like incredibly antithetical to the culture we've created where, you know, we're, we're rigidly organized and kids aren't, you know, it's, it's hard. It's hard for kids to, it's hard for parents to allow kids to have.

Those big emotions when they weren't allowed to have those big emotions, and there's like a cycle that's incredibly hard to break.

[00:20:58] Gabor Maté, MD: Yes, and um, that's why the subtitle of my book is Toxic Culture, because I think this culture is in so many ways actually a poison for people, including the culture and parenting environment, not the fault of the parents, we're talking about a large social phenomenon here.

in the schools and so on. So we created a toxic culture. And then you wonder, why are so many kids self cutting? Why is the rate of childhood suicide going up? Why are more kids depressed? Why are more and more being medicated for ADHD? Why the rise in oppositional defiant disorder and all these so called nonsensical disorders that we label and diagnose kids with?

Why? Because the parenting environment has become so strenuous and parents are not able to provide for those. Irreducible needs of the children, not because they don't love their

[00:21:50] Hunter: kids. Yeah. I mean, you, you underscore that throughout the book, the myth of normal, like that parents aren't at fault for all of these things that we have these pressures and structures in modern day life that, that are undercutting our good intentions.

You know, there's in the United States in particular, parents have incredible like lack of safety net. We, you know, parents have so much stress. And having zero support for parents and kids really and and their efforts and all these different structures that that just kind of undermine these different things.

I mean, for me, I have a lot of genuine, you know, privileges. I guess you would say that for my kids that I that they have, um, They had time to play and all these different things. Yeah, there were all these things like, my kids had time to play, but they'd go out into a neighborhood to play and there would be no other kids out there playing because of sort of the structures and the way our society has developed.

Um, yeah, I mean, tell us a little more about that. The way our culture is like this toxic individualistic culture. And so we tend to say, oh, my gosh. My kid isn't getting X, Y, Z, that Gabor Monte says they need, I'm blaming, they're blaming themselves. Tell us a little bit more about the society at large that is adding to this.

[00:23:05] Gabor Maté, MD: Well, um, let's talk about the immediate and practical sense in which society reaches kids. So now we have the social media and, and the dictatorship of technology. And, um, when you look at what social media does. If you look at something like Facebook, it tells us what's missing in our kids lives. Because on Facebook, what do you have?

You have friends. And on Facebook, what do people do? They like each other. Now, friends and liking are attachment dynamics. Our kids are so devoid of genuine attachments, that they create ersatz, false attachments on technology. Which is incredibly addictive. As a matter of fact, the technology companies do something called neural marketing.

Targeting the nervous system of the child to hit them with applications that are deliberately addictive. And this has been shown. So now we have the monster of technology reaching into your very home, abducting your kid's attention. In a very addictive way. Which completely undermines the authority of the parents.

And the ability of the parents to transmit their values and, um, their preferences to the child.

[00:24:31] Hunter: And that's

[00:24:31] Gabor Maté, MD: normal. This is normal. And we see, as I said before, we see one or two year olds with these gadgets, which actually interferes with their healthy brain development. You know that as well. And so our, what is this a sign of?

Kids are so desperate for attachment that they have to reach out to strangers on a gadget to be liked. And then they're so affected by what other people think of them. So all the bullying and the dissing and all the negative talk that goes online has such an impact on children because that's where they're looking for self validation is to the peer group, to the technology, rather than to their own independent activity in the world and their relationship with nurturing adults.

This is considered normal. I think I'm hearing

[00:25:20] Hunter: you say that, like, for, for us parents, like, there's that, you know, it kind of goes back to the title of the book you wrote with, uh, Gordon Neufeld, like, hold on to your kids, right? Like, there's a sense of, like, literally hold on to them, that attachment, right?

That make this a priority, this loving acceptance. And then also don't necessarily give them away. To the structures of society. Yeah. Like may be very careful, very slow. How you do that as far as you know, very, very mindful about the choices you make

[00:25:55] Gabor Maté, MD: with those. Well, if I was a parent these days, I wouldn't have the technology anywhere in my house, except in my own locked office.

I wouldn't let children go near. Not until they're old enough to handle. And, um, of course, on the other hand, for stressed parents, who don't have the communal support anymore, and they don't have the grandparents and the grandmothers, you know, grandfathers, uncles, aunts around the community, to help parent their kids, it's such a relief to have our kids immersed in technology.

We get a bit of space. So I understand the drive. So on the one hand, this isolated parenting, this disconnected, non communal parenting, which is completely unnatural from the point of view of human evolution, is the rule. And on the other hand, the technology provides both kids and parents an escape from the stress of isolation.

So on the one hand, the breakdown of communality in our culture creates the problem. And on the other hand, the technology comes along to provide a false solution. It's a real trap.

[00:27:05] Hunter: Stay tuned for more Mindful Mama podcasts right after this break.

I agree. I agree completely. Well, I don't want to leave the listener with, uh, on the, the load off. There's so much in this book. You should definitely get it and read it. Maybe we could go highlight some of the, some of the healing principles. Can you tell us about the four A's?

[00:27:30] Gabor Maté, MD: Look, um, what we haven't talked about in this interview, we've been focusing on child development and child rearing, so the healing part of the book, but the book is about much more than just child rearing and child development and so on.

But it's about everything. It's also about what we call addictions or mental health issues or physical health issues as a physician. I'm concerned about what makes people healthy and whole and what undermines that. And I'm saying that the same toxic influences that blight or parenting also play out in people's lives and that much of the illness, mental or physical, is based on childhood wanding.

And that can be healed. So when you talk about the four principles... I'm no longer talking about parenting so much as self parenting, and uh, what are the necessary qualities for that? Well, When I look at people with physical illnesses like autoimmune diseases, and by the way, um, there's this big mystery about why is it that women have 78 percent of autoimmune disease, where the immune system attacks the body, like rheumatoid arthritis, or ulcerosis, or colitis, Crohn's disease, onyctratine, chabromyalgia, other go on, uh, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and so on.

Women have 70 80%. Why? Because they're the ones in this society who are most, um, A culture to suppress their own emotions, including their healthy anger, not to put up boundaries and to take on the emotional needs of others. And those traits are characteristic of people who develop autoimmune disease. And often why women, because part of the toxicities of this culture is that lays that burden of being the emotional stress absorbers of everybody on women.

My wife can and does tell you a lot about, you know, on marriage. Just so for a long time, she took it on herself to kind of take care of my stresses, but that comes at a cost to herself. And so, um, when it comes to healing, agency simply means that, no, I'm not going to be governed by what social society expects of me.

I'm gonna be my own agent. If I get ill, I may take advice, but I'll be in charge. I'll decide what's right for me and what isn't. In my own life, I ask a simple question. Where in your life do you not say no when there's a no that wants to be said and you don't say it? Well, a lot of people don't know how to say no.

Because, and incidentally, by the way, as a parent, you'll know this, what's the first thing your kid said when they're a year and a half? Uh,

[00:30:08] Hunter: well, first it was tat, and then, or cat, and then it was

[00:30:11] Gabor Maté, MD: no. And it was no. There's a reason for it. Because nature knows that if you don't know how to say no, your yeses don't mean anything at all.

So the no is the next boundary. A lot of people in this society have trouble saying no. One of my earlier books is entitled When the Body Says No. When you don't know how to say no, the body will say it in the form of illness. And that's what a lot of illness is all about actually. And, uh, so agency means being able to say no.

Let's say I blew into town and I phoned you up and I said, Hey, hand me a cummy of coffee. But you're up all night with one of your kids who was sick, and you're tired. You didn't feel like having coffee, but you were too concerned with how I would feel. You were convinced that your job is to work, not to disappoint me.

And so you don't say no. That's going to have an impact on you. That means you don't have any agency. You can't even say no when your body is screaming at you to go to bed and sleep. And so agency is just being able to set our own boundaries, expecting, not expecting, experiencing and expressing our own preferences and needs.

Anger is a second essential quality. A lot of people who get sick, they don't know how to express healthy anger. I'm not talking about destructive rage. I'm talking about healthy anger, which simply says, no, you're in my space, get out. Healthy anger is a boundary defense. There's a study out of, uh, Wash, uh, Massachusetts.

They looked at 2, 000 women over a 10 year period. Um, those women that were unhappy in their marriage and didn't talk about it were four times as likely to die as those women who were unhappily married but did express their emotion. So the non expression of emotion is a real risk factor for physical illness, for reasons I can't go into now, but it's physiological, straightforward, and scientific.

So anger, healthy anger, is essential, a boundary defense.

[00:32:11] Hunter: Thank you for saying that. I think it's so important that it be said and people understand that.

[00:32:15] Gabor Maté, MD: Yes. And that's why we mustn't suppress kids anger because we want them to grow up in touch with their emotions. That doesn't mean they have the right to throw plates at the dog or to hit their siblings.

I'm not talking about that. I'm talking about the emotion itself. We have to learn, we have to help kids learn not to suppress their emotions, but to be able to experience them and to regulate them. And you do that not by suppression, but by emotional acceptance and support. So agents and, um, and, and anger are two of those A's.

And, and in the last, the longest section of the book is actually about healing. If it's parenting advice people are looking for, I do suggest the book that you already mentioned that I wrote with Gordon, his brilliant work, Hold On To Your Kids, Why Parents Need To Matter More Than Peers. The Myth of Normal talks about the needs of children and health for health and development, but it's not so much a parenting book.

It's a look at the whole course of development and the whole culture and healing. In fact, Gordon and I are writing two new chapters now for Hold On To Your Kids based on what we've learned from COVID epidemic. And one point I'll quickly make is people thought about the devastating impact of COVID.

It's not so. On, on children. The devastation of COVID on children's development depended purely on their relationship with their parents. Those kids are connected to their parents. The parents had to stay home from work. Those parents really appreciated it. I talked to many of them. I said, I actually got to see my kids milestones.

I got to see how they were learned, how they learn, how they play. I got to be with them, deepen our relationship. And for those kids, it was a benefit. But those kids that were completely hooked into the peer group because they had lost their relationship with the parents, being separate from the peer group was sheer torture and a setback.

So even the impact of the COVID isolation is differential based on children's relationships. Children that were ensconced in the peer group, got their sense of value and meaning through peer acceptance, which is a negative quality actually, if we're depending on it, they really suffered. And those kids who.

Where the parents had the privilege, maybe economically or psychologically, to really use the time to connect with their kids, to, to enjoy them. Those kids really benefited, actually. Yeah, Bor, thank

[00:34:42] Hunter: you so much for sharing some of the myth of normal with us. I've really enjoyed it and for, for talking to us for the Raising Good Humans Summit.

I think that there's so many insights here that you could. You know, watch back over again and learn the second time around. Um, thank you for sharing your time and for, for sharing your insights and, and all that I'm, I'm really honored and appreciate it enormously.

[00:35:09] Gabor Maté, MD: Thank you. And I wish you all the best with the publication of your book.

[00:35:20] Hunter: I hope you liked this episode. Wow. I mean, it really. hit me obviously pretty intensely. I felt that pretty intensely as we went through that conversation. Um, I so appreciate Dr. Mate's work and I think it's so, so important to talk about and discuss and explore in our lives. So I hope you've got some people that you think can benefit from this episode and that you will share it with them.

Send them a link in a text message, maybe right now and say, let's talk about this. That's what I do. I don't know about you, but, um, yeah, anyway, I think it's worth sharing, right? Like we need to have these conversations. This is important. And I'm so glad that you are here on this journey. So that we can evolve parenting and really make incredible positive changes in the world.

So rock on for you for being here. I'm psyched. Okay. I hope you loved this episode. I loved it. I'm so glad I can share it with you and thank you for listening. I wish you peace, ease, joy this week. If you're having a really challenging time, um, and if you're going through some of those Some of those pits and valleys, you know, you're not alone, okay?

And I'm glad that this podcast can join you and enter your world in the small way that it does, and I hope it makes a difference. So wishing you all the good things. I hope you can turn your attention to what appreciating, turn your attention to, you know, beautiful things in nature that you can find, even if it's just that powerful little weed, like bumping up through the.

Sidewalk crack that makes you realize how powerful life is and, um, wishing you a beautiful week, my friend. Thank you for listening. Namaste.

I'd say definitely do it. It's really helpful. It will change your relationship with your kids for the better. It better. And just, I'd say communicate better as a person, as a wife, as a spouse. It's been really a positive influence in our lives. So definitely do it. I'd say definitely do it. It's so

[00:37:42] Gabor Maté, MD: worth

[00:37:43] Hunter: it.

The money really is inconsequential when you get so much benefit from being a better parent to your children and feeling like you can Connecting more with them and not feeling like you're yelling all the time or you're like, why isn't this working? I would say definitely

[00:37:59] Gabor Maté, MD: do it. It's

[00:37:59] Hunter: so, so worth it.

It'll change you. No matter what age someone's child is, it's a great opportunity for personal growth and it's a great investment in someone's family. I'm very thankful I have this. You can continue in your old habits that aren't working or you can learn some new tools and gain some perspective

[00:38:22] Gabor Maté, MD: Everything in your parenting.

[00:38:27] Hunter: Are you frustrated by parenting? Do you listen to the experts and try all the tips and strategies, but you're just not seeing the results that you want? Or are you lost as to where to start? Does it all seem so overwhelming with too much to learn? Are you yearning for community people who get it, who also don't want to threaten and punish to create cooperation?

Hi, I'm Hunter Clark Fields, and if you answered yes to any of these questions, I want you to seriously consider the Mindful Parenting Membership. You'll be joining. Hundreds of members who have discovered the path of mindful parenting and now have confidence and clarity in their parenting. This isn't just another parenting class.

This is an opportunity to really discover your unique, lasting relationship, not only with your children, but with yourself. It will translate into lasting, connected relationships, not only with your children, but your partner too. mindfulparentingcourse. com

MindfulParentingCourse. com to add your name to the waitlist so you will be the first to be notified when I open the membership for enrollment. I look forward to seeing you on the inside. MindfulParentingCourse. com

Support the Podcast

- Leave a review on Apple Podcasts: your kind feedback tells Apple Podcasts that this is a show worth sharing.

- Share an episode on social media: be sure to tag me so I can share it (@mindfulmamamentor).

- Join the Membership: Support the show while learning mindful parenting and enjoying live monthly group coaching and ongoing community discussion and support.